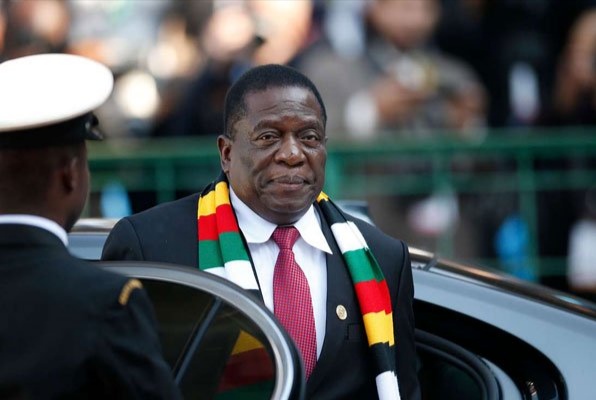

President Emmerson Mnangagwa shocked the nation last week by declaring he would not seek a third term. Addressing hundreds of Mutare residents, Mnangagwa stated, “I did my first five years, so I am serving my last five years.”

He continued, “I will complete soon and I will go to rest. We will go to congress and look for someone who will succeed me. My days to rest are close; we will go to congress and choose the one who will follow my footsteps.”

This announcement came amidst the rising popularity of the ED 2030 slogan at Zanu PF functions. Figures like Midlands Provincial Minister Owen Mudha and the Masvingo provincial youth league championed this slogan. It also came amid rumors of fissures between Mnangagwa’s camp and his powerful deputy, Constantino Chiwenga. Chiwenga is believed to harbor ambitions for the presidency and has not supported the 2030 slogan. Chiwenga, the man behind the November 2017 coup, had set his sights on taking over when Mnangagwa’s terms lapse in 2028.

Mnangagwa’s second deputy, Kembo Mohadi, had already endorsed the 2030 slogan at a youth day event earlier this year. Given Mnangagwa’s reputation, often nicknamed “Garwe” (crocodile) for his perceived pretentious character, his announcement to abandon the 2030 agenda should be met with caution. Mnangagwa has a well-documented history of saying one thing and doing another. African politicians often claim to bow to the will of the people. Even former United States President Barack Obama once said he could have easily continued in power if the people wanted him to. Thus, Mnangagwa’s declaration to rest after two terms could be a strategy.

Those in Zanu PF leading the 2030 campaign might continue, and Mnangagwa could later return and say, “I had wanted to rest, but the people have spoken, and I will respect their wish.” The key players of the ED 2030 campaign are Mnangagwa’s closest allies. It will be foolhardy to believe that they were not sent by him. Or at least if he did not want another term, he could have silenced them privately. There are claims that Mnangagwa may not seek a third term but might instead extend his current term to 2030.

This could be achieved by either postponing the presidential elections when they are due or by pushing for a constitutional amendment. The amendment could change the presidential term from the current five years to seven. These moves are seen as efforts to accommodate and fulfill his “2030 ndinenge ndichipo” (I will still be there in 2030) vision. All these moves mirror the political tactics of the late former President Robert Mugabe. Mnangagwa, having been behind many of Mugabe’s strategies, understands these games well.

Mnangagwa’s decision to announce his political retirement also follows a series of security breaches targeting his sons Tongai and David, both deputy ministers. While the intentions behind these actions are not clear, the pattern suggests a broader strategy against Mnangagwa. This potentially influenced his decision to publicly state his lack of interest in extending his presidency beyond 2028. While Mnangagwa’s statement may appear definitive, it is prudent to remain skeptical. His political maneuvers and the broader context of intra-party dynamics suggest that his declaration might be more strategic than sincere.

As 2028 draws closer, Mnangagwa’s true intentions will become clearer. The need to make constitutional changes means the work has to start now.

![2025 National Budget Statement [Download]](https://openparly.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Witholding-tax-on-Betting-2-420x280.png)